Part 10, Chapter 6: “What is to Be Done?” Poverty and

Economic Inequity in Putnam’s _Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis_.

After detailing aspects of economic inequity through the

lenses of family, parenting, schools, and community in his book Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis, Robert

Putnam attempts a closing chapter that offers possible actions for addressing

growing economic gaps and opportunity gaps in contemporary American society.

Progress in such equity may be difficult, given “growing

class segregation” which may lead to less

|

| Search "Putnam" to read my other installments on this book, my connections to it, and how it can help you grow a social justice agenda. |

One practical solution that might hit American Capitalists

in their dominating ethos is the notion of “opportunity costs,” a socioeconomic

explanation of how the opportunity gap hurts all citizens, not just the poor,

especially in terms of money spent or wasted (231). Putnam argues that “investment in poor kids

raises the rate of growth for everyone, at the same time leveling the playing

field in favor of poor kids” (231). But is “everyone” a strong enough concept

for Capitalists to embrace reform, especially in America’s hyper-competitive capitalism

that favors notions of winning and losing? In such a system, does anyone who

has more than someone else want to favor the field for someone who has less?

Even though much research suggests raising up the bottom will elevate most

everyone, I am not sure American society is willing to give up its fierce

concept of competition and conspicuous consumerism. Even if, as Putnam argues, “Writing off such a

large fraction of our youth is an awfully expensive course of inaction,” it

might be an expense many well-off Americans are willing to absorb to keep their

status, their perceived edge (233).

After attending to opportunity costs, Putnam revisits his

earlier chapters in order, providing specific suggestions that would require

the redistribution of tax funds (231) he calls for in this chapter’s opening

pages:

Family:

1.

Facilitate family planning such that the

American norm becomes “childbearing by design” rather than “by default” across

social strata (245).

2.

Expand tax credits like the Earned Income Tax

Credit and the child tax credit.

3.

Protec/strengthen social programs like food

stamps, housing vouchers and child care that provide “safety net” services.

4.

Reduce incarceration for nonviolent crimes.

5.

Enhance rehabilitation services (245-248).

Parenting:

1.

More parental leave

2.

Nix welfare policies requiring mothers to work

in the first year of a baby’s life.

3.

Provide affordable, high-quality, center-based

daycare for low-income families.

4.

Make sure daycare teachers are well-trained and

well-paid.

5.

Create “wraparound” family services (248-251).

Schools:

1.

Shrink growing residential segregation by moving

kids, money, and/or teachers to different schools.

2.

Revisit the negative impacts zoning regulations

and home mortgage deductions have on residential segregation.

3.

Publicly subsidize mixed-income housing.

4.

Keep high-quality teachers in poor schools.

5.

Create school cultures in which such teachers

can teach rather than babysit.

6.

Extend school hours to offer more

extracurriculars and enrichment opportunities.

7.

Put social and health services in schools

serving poor children.

8.

Support the notion of neighborhood schools.*

9.

Reinvest in vocational education at the

secondary and post-secondary levels.

10.

Strengthen the abilities of community colleges

to better serve poor communities (251-258).

Especially in late 2015, as presidential election season gears

up, many may read this list and connect it to the tone of certain candidates’

agendas.

Reconfiguring the tax code and redistribution of wealth sounds very much

like what we hear from Bernie Sanders, but it also might recollect what we hear

many in the media say will keep him out of the presidency. I hearken back to

Hillary Clinton’s dismissive tone regarding Sanders’ big ideas and her

reiteration of the phrase “I know how to get things done” in the recent

Democratic debate. In that phrase and the disbelief I see surrounding Sanders’

social change agenda, I see those old notions of American Capitalism where it

is just a “given” that big-money interests have to be placated for any sort of

change, and only the modicum of social change can trickle down to those most in

need because big profiteers need to keep profiting, and to do that, some have

to win and some have to lose. I noticed Hillary Clinton using the rhetoric of

the American Dream, the bootstrap narrative, too. To enact many of the social

programs and reconfigurations of tax systems and other systems where private

money is involved (see prisons, and, more and more frequently, public schools),

we will have to acknowledge the myth of the American Dream and stop embracing

as reality something that reifies the old systems of socioeconomic

inequalities.

Furthermore, when we see politicians continue to invest in

the mythos, we need to be especially critical of why they are doing so.

Regarding the “schools” suggestions, I was less fraught over

Putnam’s suggestions than I expected. The community college suggestions seem to

align with President Obama’s push to bolster the import of community colleges. Putnam

does mention charter schools as a possible solution when he talks about

neighborhood schools (*), which can be worrisome if one thinks that is where

the bulk of Putnam’s reform efforts reside. I however, found more promise in

the notion of transforming public schools into bustling community centers.

|

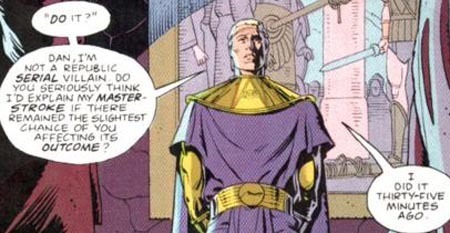

| An image of American cultural values or one which challenges them? |

Imagine a school open

24 hours a day, with a wide range of health care services not housed only in

hospitals, but in clinic spaces on grounds. Imagine, even, cafeterias open all

day and constant access to showers and even sleeping spaces. Surely our

existing budgets and cultural expectations of schooling do not provide for this

sort of scenario, and I would never advocate for teachers’ work days to be

extended such that they see themselves working at a boarding school, but I see

great potential in making every public school more of a support ecology, a

built-in societal safety net, than they currently exhibit. I do not pretend to

have the details worked out – and a lack of practical strategies beyond basic

suggestions certainly dominates this chapter -- but I believe the best transformative

practices Putnam offers reside in the notion of transforming schools into vibrant,

always-active community centers.

Community:

1.

Provide extracurricular opportunities free of

economic hardships via pay-to-play policies.

2.

Fund high-quality mentoring programs, perhaps

via the Ameri-Corps program.

3.

Move poor families to better neighborhoods

(258-260).

4.

Restore working-class wages.

Putnam closes with a refrain of his key appeal: That if we

want to improve the lives of poor children, we need to see them as belonging to

all of us. All kids need to be seen as “our kids,” as Putnam suggests once

seemed the case. He states that even those who still buy in to Emersonian

notions of self-reliance and other seemingly quintessentially American notions

like manifest destiny, rugged individualism, and the American Dream’s work

rhetoric “should acknowledge our responsibility to these children. For America’s

poor kids do belong to us and we to them” (261). Low on details but full of

possibilities, this final chapter is more guidepost than atlas, but better to

work with scant direction than have no awareness at all of current pathways deleterious

to so many and already closing in on our most vulnerable children and families.