AND eager for your help. Have a story of power, manipulation, self-interest or injustice which needs attention? Let me know and we'll let the world discover "what's that smell."

"If you're a profession of sheep, then you'll be run by wolves." -- David C. Berliner

"Journalism is printing what someone else does not want printed: Everything else is public relations." -- George Orwell

"Washing one's hands of the conflict between the powerful and the powerless means to side with the powerful, not to be neutral." -- Paulo Freire

PUBLIC SERVICE ANNOUNCEMENT! ;)

Wednesday, November 4, 2015

Critiquing the Meritocracy: Two Good Reads

I encourage you to read the following two short pieces and consider them in relation to poverty, schooling, and society. One is entitled "Don't Give My Kid an Award." Written by a conscientious mother, this text is an example of someone with privilege explicating that privilege while using her son's schooling experience as a vignetted informal case study. The other, "How the Myth of Meritocracy Ruins Students," reveals how even the most liberal and open-minded "check your privilegers" benefit from embracing the meritocracy mindset, at the expense of more-vulnerable citizens.

Friday, October 16, 2015

_Our Kids_ Reflections, Part 10: Chapter 6: "What is to Be Done?"

Part 10, Chapter 6: “What is to Be Done?” Poverty and

Economic Inequity in Putnam’s _Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis_.

After detailing aspects of economic inequity through the

lenses of family, parenting, schools, and community in his book Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis, Robert

Putnam attempts a closing chapter that offers possible actions for addressing

growing economic gaps and opportunity gaps in contemporary American society.

Progress in such equity may be difficult, given “growing

class segregation” which may lead to less

|

| Search "Putnam" to read my other installments on this book, my connections to it, and how it can help you grow a social justice agenda. |

One practical solution that might hit American Capitalists

in their dominating ethos is the notion of “opportunity costs,” a socioeconomic

explanation of how the opportunity gap hurts all citizens, not just the poor,

especially in terms of money spent or wasted (231). Putnam argues that “investment in poor kids

raises the rate of growth for everyone, at the same time leveling the playing

field in favor of poor kids” (231). But is “everyone” a strong enough concept

for Capitalists to embrace reform, especially in America’s hyper-competitive capitalism

that favors notions of winning and losing? In such a system, does anyone who

has more than someone else want to favor the field for someone who has less?

Even though much research suggests raising up the bottom will elevate most

everyone, I am not sure American society is willing to give up its fierce

concept of competition and conspicuous consumerism. Even if, as Putnam argues, “Writing off such a

large fraction of our youth is an awfully expensive course of inaction,” it

might be an expense many well-off Americans are willing to absorb to keep their

status, their perceived edge (233).

After attending to opportunity costs, Putnam revisits his

earlier chapters in order, providing specific suggestions that would require

the redistribution of tax funds (231) he calls for in this chapter’s opening

pages:

Family:

1.

Facilitate family planning such that the

American norm becomes “childbearing by design” rather than “by default” across

social strata (245).

2.

Expand tax credits like the Earned Income Tax

Credit and the child tax credit.

3.

Protec/strengthen social programs like food

stamps, housing vouchers and child care that provide “safety net” services.

4.

Reduce incarceration for nonviolent crimes.

5.

Enhance rehabilitation services (245-248).

Parenting:

1.

More parental leave

2.

Nix welfare policies requiring mothers to work

in the first year of a baby’s life.

3.

Provide affordable, high-quality, center-based

daycare for low-income families.

4.

Make sure daycare teachers are well-trained and

well-paid.

5.

Create “wraparound” family services (248-251).

Schools:

1.

Shrink growing residential segregation by moving

kids, money, and/or teachers to different schools.

2.

Revisit the negative impacts zoning regulations

and home mortgage deductions have on residential segregation.

3.

Publicly subsidize mixed-income housing.

4.

Keep high-quality teachers in poor schools.

5.

Create school cultures in which such teachers

can teach rather than babysit.

6.

Extend school hours to offer more

extracurriculars and enrichment opportunities.

7.

Put social and health services in schools

serving poor children.

8.

Support the notion of neighborhood schools.*

9.

Reinvest in vocational education at the

secondary and post-secondary levels.

10.

Strengthen the abilities of community colleges

to better serve poor communities (251-258).

Especially in late 2015, as presidential election season gears

up, many may read this list and connect it to the tone of certain candidates’

agendas.

Reconfiguring the tax code and redistribution of wealth sounds very much

like what we hear from Bernie Sanders, but it also might recollect what we hear

many in the media say will keep him out of the presidency. I hearken back to

Hillary Clinton’s dismissive tone regarding Sanders’ big ideas and her

reiteration of the phrase “I know how to get things done” in the recent

Democratic debate. In that phrase and the disbelief I see surrounding Sanders’

social change agenda, I see those old notions of American Capitalism where it

is just a “given” that big-money interests have to be placated for any sort of

change, and only the modicum of social change can trickle down to those most in

need because big profiteers need to keep profiting, and to do that, some have

to win and some have to lose. I noticed Hillary Clinton using the rhetoric of

the American Dream, the bootstrap narrative, too. To enact many of the social

programs and reconfigurations of tax systems and other systems where private

money is involved (see prisons, and, more and more frequently, public schools),

we will have to acknowledge the myth of the American Dream and stop embracing

as reality something that reifies the old systems of socioeconomic

inequalities.

Furthermore, when we see politicians continue to invest in

the mythos, we need to be especially critical of why they are doing so.

Regarding the “schools” suggestions, I was less fraught over

Putnam’s suggestions than I expected. The community college suggestions seem to

align with President Obama’s push to bolster the import of community colleges. Putnam

does mention charter schools as a possible solution when he talks about

neighborhood schools (*), which can be worrisome if one thinks that is where

the bulk of Putnam’s reform efforts reside. I however, found more promise in

the notion of transforming public schools into bustling community centers.

|

| An image of American cultural values or one which challenges them? |

Imagine a school open

24 hours a day, with a wide range of health care services not housed only in

hospitals, but in clinic spaces on grounds. Imagine, even, cafeterias open all

day and constant access to showers and even sleeping spaces. Surely our

existing budgets and cultural expectations of schooling do not provide for this

sort of scenario, and I would never advocate for teachers’ work days to be

extended such that they see themselves working at a boarding school, but I see

great potential in making every public school more of a support ecology, a

built-in societal safety net, than they currently exhibit. I do not pretend to

have the details worked out – and a lack of practical strategies beyond basic

suggestions certainly dominates this chapter -- but I believe the best transformative

practices Putnam offers reside in the notion of transforming schools into vibrant,

always-active community centers.

Community:

1.

Provide extracurricular opportunities free of

economic hardships via pay-to-play policies.

2.

Fund high-quality mentoring programs, perhaps

via the Ameri-Corps program.

3.

Move poor families to better neighborhoods

(258-260).

4.

Restore working-class wages.

Putnam closes with a refrain of his key appeal: That if we

want to improve the lives of poor children, we need to see them as belonging to

all of us. All kids need to be seen as “our kids,” as Putnam suggests once

seemed the case. He states that even those who still buy in to Emersonian

notions of self-reliance and other seemingly quintessentially American notions

like manifest destiny, rugged individualism, and the American Dream’s work

rhetoric “should acknowledge our responsibility to these children. For America’s

poor kids do belong to us and we to them” (261). Low on details but full of

possibilities, this final chapter is more guidepost than atlas, but better to

work with scant direction than have no awareness at all of current pathways deleterious

to so many and already closing in on our most vulnerable children and families.

Sunday, October 4, 2015

On Presidential Endorsements, Neutral Stances, and "New-Trail" Stances

The NEA has joined the AFT in endorsing Hillary Clinton as the choice presidential candidate, *despite many members' objections.* Meanwhile, other professional organizations in teaching and teacher education continue to ride out their "neutral" stances on Common Core and associated education reform measures of the Clinton-Bush II-Obama era.

With so much evidence of cabal/cartel-style, dim-luminati "leadership" at play, what's a dog to do? Education Reform-Critical Boxer has this advice:

Me? I might advise doing a Google search for "quotes on starting new." Shelley comes to mind as well:

With so much evidence of cabal/cartel-style, dim-luminati "leadership" at play, what's a dog to do? Education Reform-Critical Boxer has this advice:

Me? I might advise doing a Google search for "quotes on starting new." Shelley comes to mind as well:

‘My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!'Nothing beside remains. Round the decayOf that colossal wreck, boundless and bareThe lone and level sands stretch far away.”

|

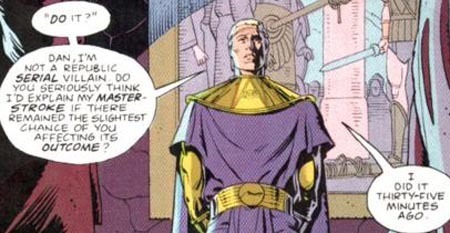

| "Endorse a presidential candidate without considering the views of my membership? I did it thirty-five minutes ago." |

Friday, October 2, 2015

Wednesday, September 23, 2015

"Race and Class Collide in a Plan for Two Brooklyn Schools": From The New York Times

Kate Taylor, reporter for The New York Times, recently published a story rife with insights in the intersectionalities of prejudice, fear, and segregationist idealisms associated with contemporary American values regarding public schools. As someone deep into the messages in Robert Putnam's Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis, I found the story fascinating.

Here's its crux: When overcrowding as P.S. 8 in Brooklyn, New York, became a concern, city officials suggested moving students from that school to nearby P.S. 307, which has more than enough space to accommodate the overflow. However, when rezoning to enact this plan was pitched, stakeholders took issue. Some simply do not want the levels of racial and socioeconomic intermingling the move would facilitate in one of America's most segregated school systems.

Read the article by clicking *here*. Marvel that some of the people quoted live in the North in 2015 and not Greensboro, North Carolina, in 1965. Note how test scores are a focus regarding defining quality schools and "quality" students.

Putnam says in Our Kids that growing housing and community segregation between the well-off and the poor presents challenges to empathy, since so few rich kids actually see kids not as well off as they do. In this story, there is a concerted effort to keep well-off children away from poorer children, to keep black and brown kids away from Anglos and people of East Asian decent. There's even palpable concern about busing as a means of achieving a racially and economically diverse student body -- with space to move and mingle!

The adults in this situation are perpetuating the mentalities that keep the American populus from addressing growing social mobility gaps and opportunity gaps. Taylor's story exemplifies the "I got mine" attitude and growing sense of insularity and "unknowability of the self from the other" that even some liberal-minded social justice groups' members use to defend exclusionary spaces.

May the members of this community see all the young people at both these schools -- attending now and attending in the near future -- as their kids, every one of them.

Here's its crux: When overcrowding as P.S. 8 in Brooklyn, New York, became a concern, city officials suggested moving students from that school to nearby P.S. 307, which has more than enough space to accommodate the overflow. However, when rezoning to enact this plan was pitched, stakeholders took issue. Some simply do not want the levels of racial and socioeconomic intermingling the move would facilitate in one of America's most segregated school systems.

Read the article by clicking *here*. Marvel that some of the people quoted live in the North in 2015 and not Greensboro, North Carolina, in 1965. Note how test scores are a focus regarding defining quality schools and "quality" students.

Putnam says in Our Kids that growing housing and community segregation between the well-off and the poor presents challenges to empathy, since so few rich kids actually see kids not as well off as they do. In this story, there is a concerted effort to keep well-off children away from poorer children, to keep black and brown kids away from Anglos and people of East Asian decent. There's even palpable concern about busing as a means of achieving a racially and economically diverse student body -- with space to move and mingle!

The adults in this situation are perpetuating the mentalities that keep the American populus from addressing growing social mobility gaps and opportunity gaps. Taylor's story exemplifies the "I got mine" attitude and growing sense of insularity and "unknowability of the self from the other" that even some liberal-minded social justice groups' members use to defend exclusionary spaces.

May the members of this community see all the young people at both these schools -- attending now and attending in the near future -- as their kids, every one of them.

Bernie Sanders On Growing Economic Inequality

In this video, when Sanders says the middle class is shrinking, he means folks once in the middle class are now living in poverty. Consider this video in relation to the posts on Robert Putnam's Our Kids that I have posted so far.

Tuesday, September 15, 2015

_Our Kids_ Reflections: Part 9; Chapter 4: “Schooling” – Concatenations & Ecologies; Knapsacks & Echoes – and Bindles & Buses?

Part 9; Chapter 4: “Schooling” – Concatenations &

Ecologies; Knapsacks & Echoes – and Bindles & Buses?

Further, Geoffrey

Canada praised the book on the back of its dust jacket. Canada, president of

the Harlem Children’s Zone, is known as a successful education reformer due to

the type of charter school he helped create in New York. Canada has kept his school

successful in part by finding ways to remove students from the school when they

fail to perform. Both Canada and Putnam

are Harvard men, Canada via graduating from the university and Putnam via

working there. Harvard brazenly positions itself at the intersections of

schooling, corporate initiative and entrepreneurial education, so I worried

Putnam might follow the lead of many other alternative schooling advocates and

place the blame for growing income inequality within and across races squarely

on the shoulders of America’s public education system.

Thankfully, he does not.

He admits that “central question[s]” of the chapter are “Do

schools in American today tend to widen

the growing gaps between have and have-nots kids,” do they reduce them, or do they “have little effect either way?” and if

schools do affect mobility, “are they causes

of class divergence of merely sites

of class divergence?” (160). His findings suggest that many of the elements of

schooling which education reformers are quick to tout as the reasons schools

are failing their communities -- bad

test scores and poorly-educated teachers, for example – are not reasons the

opportunity gap continues to grow. In short, schools reflect growing

socioeconomic stratification, but, generally speaking, are not a cause of it.

Kids are more likely to suffer from extenuating

circumstances affecting their schooling than from schools themselves. For

example, Putnam discusses how kids from more-educated parents might have access

to more “institutional savvy” when it comes to navigating course selection,

extracurricular participation, or knowing what it takes to get into college

(157).

Regarding standardized testing, many conscientious educators

have known for years that such tests’ scores correlate most strongly with zip

code, salary, and education. That is to say that most standardized tests tell

us very little about learning but tell us much about what part of town in which

a kid lives and how much money and education his or her parents might have.

Citing a study by Stanford’s Sean Reardon (For what it is worth, Stanford has a

reputation for entrepreneurial education reform as well as does Putnam’s home

university), Putnam points to a “widening class gap in both math and reading

scores among American kids in recent decades” (161). As with many other aspects

of American living, “this class gap has been growing within each racial group,

while the gaps between racial groups have been narrowing” (161). Unlike many of

the other factors in which this scissor effect is apparent, test scores do not

matter that much in the long run, anyway, though certainly current education

policies push parents and teachers into thinking they are more important than

they are.

Indeed, Putnam says of Reardon’s study that it suggests “that schools

themselves aren’t creating the opportunity gap: the gap is already large by the

time children enter kindergarten” (162).

Despite evidence that schools do not seem to perpetuate

mobility gaps, multiple studies suggest “exceptionally wide differences in

academic outcomes between schools attended by affluent kids and schools

attended by their impoverished counterparts” (163). If schools are not

nurturing this inequality, what is?

Putnam points first to “residential sorting” (163), the

housing segregation he mentioned in previous chapters and which I have

discussed in previous reflections. Neighborhood reputations and even housing

costs are associated with “good schools” in the competitive American mindset.

With communities more segregated by income than ever before, so much so that

Putnam claims well-off kids may never see poorer kids and therefore be less

likely to recognize that poverty exists or sympathize with those less

fortunate, compounding social inequities, is it surprising to note that poor

kids and more-affluent kids attend separate schools at greater rates now than

in the 1950s Putnam glorifies (163)?

Anticipating that advocates of school choice might interpret

this information as relevant to their agendas, Putnam states that school choice

would “not likely” make a difference to the lower-class kids he profiles in his

chapters. Yet again my worries that pro-education reform sentiments would

proliferate in this chapter were proved unfounded.

Turning to the work of Orfield and Eaton, Putnam reveals that,

often, “poor kids achieve more in high-income schools” and this phenomenon is a

consistent research finding. Indeed, some studies suggest high school kids’

learning may correlate more strongly with their classmates’ family

backgrounds than with their own (165)!

|

| Immediately, I thought of busing along socioeconomic lines as a possible solution to social mobility inequity. Putnam does not mention it, however. Why? |

Based on this consistency, I have to wonder if a new wave of

busing regulations need to be introduced in public education. Is it time for

socio-economic busing?

Much evidence suggests busing programs helped desegregate

schools by race, obviously, and that, perhaps less obviously, desegregation was

positive for minority students and for school populations overall. Could

busing poor children to affluent districts and affluent students to less

affluent districts be a concrete means of addressing the growing housing and

community segregation Putnam sees in American society, a means of returning

American adults’ mindsets to those that see all kids as their kids? Perhaps,

but, puzzlingly, Putnam never mentions busing along socioeconomic lines in Our Kids.

Instead, Putnam tries to explain why “the socioeconomic

composition of a school seem[s] to have such a powerful impact on its students”

(165). He assumes some may hypothesize that school financing must offer some

explanation. Since schools in richer districts have more money via higher

|

| Can the most famous part of this text be a means of exploring poverty? Is the parallel to the stresses of war and the stresses of poverty fair? |

Rather -- recall the quote about kindergarten from above

paragraphs – “the things that students bring with them to school” matter much

more regarding opportunity gaps. The plight of poor American school children is

much less akin to any Jane Austen novel and more akin to *Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried. *

Schools in affluent areas have more

parental involvement and may house kids less affected by drugs, homelessness,

crime and other heavy stresses. This means kids are influenced by fewer

children experiencing these odious aspects as well. Parents in high-income

areas “demand a more academically rigorous curriculum” (168) – probably because of their institutional

savvy! As many as three times the number of AP classes are offered in

higher-income area schools compared to others, says Putnam (168). While state

financing may not exacerbate inequality, what Putnam calls “para-school

funding” does (167). More affluent communities are able to pour more funds not

allocated by the government into schools. In this instance, kids in

lower-income schools suffer because of what they can’t carry: extra income.

Peer pressure is noted as important too. That is, kids contribute to a school’s

culture as one in which there is a drive to do well. But, as Putnam reminds,

this mindset also most likely derives from the standards set by affluent

parents (169).

|

| The In/Visible Bindle as metaphor for the things poor kids carry and for what they can't carry to school. Too on the nose or perfect for a poverty-first social justice agenda? |

A “concatenation of disadvantage” – the things they carry

and the things they cannot carry – keeps kids from doing as well as they could

if they had more access to wealth and opportunity (171). The concatenation of

disadvantage, comprised of multiple stresses, “intrude[s] into the classroom in

high poverty schools,” says Putnam in a particularly poignant and poetic turn

of phrase. Whereas I might continue the O’Brien reference to embrace an

economics-based version of Peggy McIntosh’s invisible knapsack – the binding

bindle? – Putnam rebrands these disadvantages as “ecological challenges” facing

high-poverty schools (173).

These ecological stresses affect teachers too, and Putnam

does parallel the thinking of education reformers who want the public to think

the teacher is the most important element of a classroom in so much as he says

that teachers may contribute to low-income schools’ producing lower-achieving

students, but he does not place blame on the teachers’ shoulders but on the

concatenation, the ecology, the brew of stresses, the “climate of disorder and

even danger” that affects them and their students and contributes to low morale,

burn out, and high turnover (173).

To sum, when it comes to the question of whether schools

contribute to the opportunity gap,

The answer is this: the gap is

created more by what happens to the kids before they get to school, by things

that happen outside of school, and by what kids bring (or don’t bring) with

them to school…than by what schools do to them. The American public school

today is a kind of echo chamber in which the advantages or disadvantages that

children bring with them to school have effects on other kids. The growing

class segregation of our neighborhoods and thus our schools means that

middle-class kids…hear mostly encouraging and beneficial echoes at school. Whereas

lower-class kids…hear mostly discouraging and harmful echoes (182).

Echoes. Loud enough to make one want to scream. Or to start

up some buses, perhaps?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)