Part 8; Chapter 3: “The American Dream: Myths and Realities”

– Explaining the Specters of Poverty

"The fundamental social significance of the neurobiological discoveries that I’ve just summarized is that healthy brain development in American children turns out to be closely correlated with parental education, income, and social class"

So begins the second half of Robert Putnam’s “Parenting” chapter

from Our Kids: The American Dream in

Crisis. Having shared *in earlier pages* the Adverse Childhood Experience

scale and introduced the John Henry Effect, wherein even those who seemed to

escape poverty and other stresses still deal with “adverse physiological

effects” due to the “wear and tear of chronic stress” (113), Putnam piles on

more evidence that the trace of poverty is at least as difficult to escape as

poverty itself.

Kids in poverty “are at greater risk for elevated levels of

cortisol,” a stress hormone that “impinges” health; emotional regulation in the

brain is influenced by stress; and, some research suggests that the reason poor

kids seem to have more trouble concentrating on a single task is because they

are struck in a sort of constant fight or flight reflex: “Their brains had been

trained to maintain constant surveillance of the environment for new threats”

(116).

Imagine being a poor student in the current age of

corporacratic education reform, with new threats of high-stakes standardized

tests, stressed-out teachers, and the constant peril of school closures! Those

of us parenting and teaching in the era of education reform need to pay close

attention to what Putnam and his colleagues’ research tells us about poverty,

stress, and growing socioeconomic gaps.

Simply put, “kids from more affluent homes are exposed to

less toxic stress than kids raised in poverty” (117), and while day-to-day

interactions among kids from different economic strata are rarer than they used

to be, do parents really want to accept a “I’ll take care of mine; you take

care of yours” approach? If we are in an age of self-interest=best-interest

parenting within the affluent classes, is such an approach truly in the best

interests of even wealthy kids? If the answer is “yes” – and it very well may

be – aren’t poor families and poor children simply out of luck?

Perhaps knowledge of the “class-based gap in parenting

styles, which has been growing significantly during recent decades,” could

offer some hope (117) – if less-affluent parents were able to take on traits of

more affluent parents, a big if given the realities of current resource

stratifications.

Citing ethnographer Annette Lareau, Putnam mentions two

distinctive parenting styles: Concerted Cultivation and Natural Growth

(118-121).

|

CONCERTED CULTIVATION/AFFLUENT PARENTING

|

NATURAL GROWTH/LESS-AFFLUENT PARENTING

|

|

·

Child rearing investments in time, activities,

etc.

·

Autonomy

·

Independence

·

Self-direction

·

Choices

·

Roughly 6:1 Encouraging/Discouraging

statements

·

Family dinners

·

Spending per child +75% since 1980s

·

Significant time w infants/toddlers

·

Kids get more “face time”

·

More common among affluent families

|

·

Development left more to kids’ own devices

·

Discipline

·

Obedience

·

Conformity to pre-established rules

·

Roughly 1:1 or even 1:2

Encouraging/Discouraging statements

·

Family members do not or cannot eat together

· Spending per child -22% since 1980s

·

Half as much time w/ infant/toddlers

·

Kids get more “screen time”

·

More common among poorer families

|

Putnam dismisses notions that child-rearing between classes

is cultural. Brain science, he says, indicates that poor parents are more harsh

and punitive in their styles “because they themselves experienced higher levels

of chronic stress” (121). Today’s poor kids are more likely than they have been

in a long time to be poor parents despite their efforts. By the time they are

parents, imagine the stress that comes from a system that seems designed to

keep one where one is rather than offers mobility for effort. Even parents who

try valiantly to embed or embody Concerted Cultivated aspects may have to live

with the knowledge that the specter of poverty is too great a haunt to

overcome. With such knowledge, though, where is hope? Without the knowledge?

Imagine a young driver learning a clutch transmission system. The one fortunate

enough to have access to the car grinds the gears. The car’s gears grind, but

it goes nowhere. If the privileged party doesn’t do something to change his or

her operating procedures, the car will grind its gears unwittingly until the

stress of the frictions wear it down and it becomes broken, sometimes beyond

repair, and not completely because of its own actions.

|

| Is being poor in America like being a manual transmission? You move or grind to a halt at the whim of the driver, but still take the blame if they wear you out? |

Regarding family dinners, we know that conversing around

food offers a means of communal rapport humans have known and valued for

thousands of years. However, poor parents often cannot “make eating together a

priority” (123) even if they wanted to. While admitting eating together is “no

panacea for child development,” Putnam asserts that “it is one indicator of the

subtle but powerful investments that parents make in their kids (or fail to

make)” (123).

“Stressed parents are both harsher and less attentive

parents,” says Putnam (130), but we must realize that very few parents actually

seek to be harsh and inattentive. Whereas affluent parents have resources,

poor, stressed parents live with scarcity. Via a book by that name,

Mullainathan and Shafir influence Putnam’s understandings:

Under conditions of scarcity, they

write, the brain’s ability to grasp, manage, and solve problems falters, like a

computer slowed down by too many open apps, leaving us less efficient and less

effective than we would be under conditions of abundance (130).

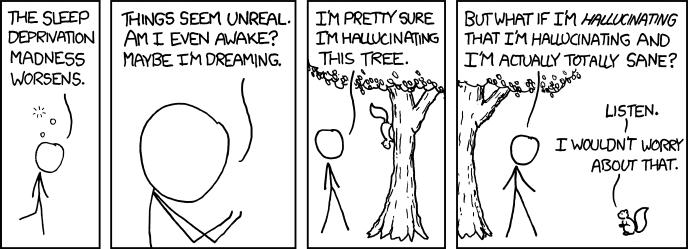

Those not as familiar with scarcity (or computers) might better

understand the world poor parents inhabit via thinking about sleep. Or, the

lack of it, actually. Any adult professional will tell you that even if they

work long hours, there comes a time when their body and mind is just worn down

by the grind of being too active for too long to try to meet a goal. Even

affluent parents should admit to not making the best parenting decisions when

they are sleep-deprived. In no unrealistic manner, less-affluent parents live

their lives in a metaphorical state of sleep deprivation, able to perform

better if only they could meet their own needs and rest easy.

But, as Putnam’s

amalgamation of the research shows, since families are less able to get out of

the cycles of poverty than in decades past, they never get that rest. They may

have been on high alert as kids, remained on high alert as adults, and are on

high alert while raising kids who are on high alert too.

Not only do specters of poverty remain, but

they compound and form boggish quagmires. Acting more like affluent parents without the resources is not be enough to resolve mobility issues. Indeed, the inverse is more likely: Solving mobility issues is likely to help less-affluent parents act more like those use the Concerted Cultivation style of parenting.

Indeed, worth noting is that favoring the habits of college-educated (remember: this is the criteria Putnam uses to describe affluent families) parents and their "results" -- the behaviors and dispositions of their children -- may only be seen as healthy or the preferred model because the power of opinion is in the hands of the wealthy. Given that so few affluent American kids interact with poor kids now compared to the 1950s, when social mobility was high within and among classes, perhaps affluent parents are producing hyper-coddled, egotists with no internal coping mechanisms once they see they're not as perfect as they might have thought. Many of us know of one or two kids from well-educated families who are over-confident assholes in no small part due to their parents' particular blend of Concerted Cultivation or meshing of the worst iterations of the two styles.

I think of some (certainly not all) of my students at Washington State University, who seemed to have left the country club of high school social life for the resort and spa of WSU. While they were eager to call foul regarding many social ills and inequity, rarely were they able to articulate their own economic privilege, except through conspicuous consumerism. Even among those who were first-generation college students or who identified as from working-class families, many admitted to me that the campus seemed to support a social pressure toward entitled that seemed to emanate from those who were economically privileged and did not have the worry of paying their own tuition bills. I remember how uncomfortable I felt on the beautiful grounds of the University of Virginia, earning my doctorate as a North Carolinian with roots in poverty but now walking among the popped collars and BMW's of nineteen-year-olds eager to get to some horse race or show off their latest dress shirt and bow tie. I think of a professoriate at large also willing to point out many inequities and inequalities but less willing to acknowledge that most of its members are from the upper-middle class, so economic value system may perpetuate in colleges. I think of helicopter parents' children who are so afraid of letting go of their support systems and bolstering resources that they have trouble with independence. I consider the push from some college kids for the coddling of required trigger warning policies and how some resist the notion of college as a place where their ideas and preconceived notions should be challenged.

But I digress...

Regardless of my extrapolations, important questions remain: If rich kids only see and interact with other rich kids, how can their mindsets be challenged? Does class segregation yield parenting with self-perpetuating pampering which reifies paupering? Surely some American kids are living the dream; others seem stuck in a dream state in which neither rest, sleep, nor comfort are afforded them, certainly not offered to them by the dominant discoursers of affluent dreamers either obtuse or unsympathetic to their realities.

No comments:

Post a Comment